Genetic Screening

Genetic counseling and screening, to be effective as a tool for mating and conceiving with safety, depends on knowledge about genes and chromosomes and the ability to interpret the mechanisms of genetic inheritance. Questions concerning the odds for those who have been assessed realistically regarding known genetic disorders broaden our appreciation of ethnic history, family history, and generational history, whether we plan to be parents or just healthy people.

Q. In genetic screening, can one see a gene?

A. No, not in human beings. You are only screening the effect of that particular gene or the product of the gene, such as an enzyme, which you can see and define chemically. You measure its activity presence or absence. That's what these tests are about.

Q. How is genetic screening done, and is it always done based on some suspicion concerning someone's background?

A. It comes about in several ways. It would be miraculous to screen every gene that one has, to know a human being's total genetic makeup by means of an overall comprehensive test. But at this time we can't do that. With respect to individual counselors, we look for particular trends in a family history. Much of the time the family history will not reveal any problems. Genetic screening in the general population is geared at testing healthy individuals, newborns or adults, for a particular genetic trait or characteristic. These tests are based on the probability that the gene is present or how common a gene is in a particular population or an ethnic group.

Q. When there is a genetic screening, what do you take from the person or what do you examine in the person?

A. Usually some body fluid such as blood or urine is taken. We examine blood or that portion of blood called serum. Serum is the colloidal fluid, if you will, of the blood itself. Sometimes we use the cells of the blood. We perform analyses on white or red cells depending on the particular disorder in question.

Q. You then take the blood from the person and analyze it, and if it doesn't do certain things it's supposed to do, that's how you know something is wrong?

A. It's not the blood itself. We're testing the components of the blood to see if it contains certain ingredients. For example, we look for certain enzymes or chemicals that are in these cells, that should be there in a certain amount. We have standards by which we can assay whether there is too little there, or just the right amount, and so forth.

Q. Does age or sex matter? For example, would you find the same components in the blood of a 70 year old as in a 30 year old?

A. For all intents and purposes, in terms of what I would be measuring, yes. Now there may be some differences in terms of amounts, but in terms of my work there would be no problem. We can also look directly at the bundles of genes or chromosomes. This would constitute another type of genetic screening test that could be performed.

Q. Is there any sort of cure for Tay Sachs disease now?

A. No.

Q. Do genes affect one's personality? Do we tend to be angry, stubborn, or mean because of our genes?

A. There are some genes that are involved with affective disorders such as manic depression. I don't know of genes affecting one's general temperament.

Q. Is schizophrenia a genetic condition?

A. There may be genetic background. Again, the individual's family history should be reviewed.

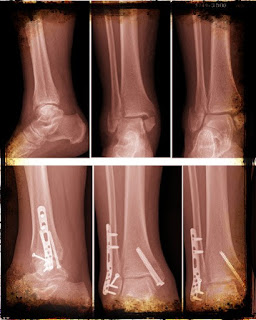

Q. Do the power and speed of the healing of broken bones have anything to do with one's genetics?

A. Yes, our different genes predispose us to react differently. We are all unique based upon our different genetic makeup. Rates of healing and the way our teeth erupt, for example, are all in part genetically determined. There are also genetically determined bone diseases.

Q. Is fortified vitamin D helpful or nourishing for bone disease?

A. It depends on the type of bone disease. Individual cases require personal consultations with the patient's doctor.

Q. When my grandson was in elementary school and the class was asked to stand up, he found he could not. He had temporary paralysis. It occurred again when he entered college. Is this condition a genetic disorder?

A. There is a genetic disease called periodic paralysis, which with proper management can be successfully handled. This is a disorder that neurologists can handle with a measure of success.

Q. Is sickle cell anemia only limited to the black population?

A. Sickle cell disease has its highest incidence in the United States in the black population, but it is certainly not limited to blacks worldwide. The incidence of sickle gene in the black American is about 8 to 9 percent. However, if you look worldwide, there are areas where there is significant incidence of sickle cell, such as the Mediterranean, Greece, the Middle East, Kuwait, and parts of India.

Q. I know blacks can have thalassemia. Can they also have Tay Sachs disease?

A. It is possible.

Q. Is genetic screening or gene testing for employment justified, or is it a device for discrimination?

A. If you have a specific health related reason for doing screening, then it's justified. If you're doing it for some vague reason without clearcut goals and objectives, then I don't think it's justified at all. When screening programs have been set up with more enthusiasm than thought, we've been burned. Occasionally, results of such tests have been used indiscriminately. So you have to be very concerned about why these tests are being done.

Q. Cystic fibrosis is reported to be a genetic disease. Can you explain the cause of this defect?

A. Cystic fibrosis today is a genetic disease. In spite of extensive research, we do not know what the basic gene defect is. The work on cystic fibrosis in the last 15 years, however, has increased our understanding of the disorder and has improved the life expectancy of affected individuals.

Q. Can prescreening or pretesting before birth establish the ratio of risk with cystic fibrosis as with a number of other genetic diseases?

A. No, at this point there is no prenatal diagnosis. The only way you can estimate the risk of inheritance is through family studies, the classic Mendelian studies. But there is a problem in going back to previous generations because cystic fibrosis was not identified as a disease until 1938, and it mimics many other diseases.

Q. What type of genetic problems do we associate with Italians and Greeks?

A. Thalassemia is the term for hemoglobin disorders that are frequent in this population, which incidentally includes people of North African extraction and also extends over to Southeast Asia and parts of India. There are different types of thalassemia, a disorder of hemoglobin synthesis.

Q. Do we come into the world with harmful genes if we have no recognizable disorders?

A. Each of us has eight or nine so-called recessive genes. These genes are mutated, changed, or altered. They are generally silent or hidden. It's important, however, to have these genes. It's not bad that you carry them. They're just there, and they're part of your makeup. I believe that genetic heterogeneity strengthens our general health.

Q. Are blood groups determined by genes?

A. Yes, they are all programmed by genes.

Q. What is meant by the slogan we sometimes see on posters that reads, "You are or may be carrying a walking time bomb?"

A. This is kind of a dramatic statement, which to me is very alarming, because we don't want to frighten people about themselves or their future. We want them to be concerned and to understand, so that they will be responsible for their future decisions. For example, if by chance you carry a particular gene and then meet and mate with someone who carries the same like malfunctioning gene, there might be a problem. People should be informed of their risks whenever possible.

Q. Can you tell us a few more factors that are involved in genetic counseling and screening?

A. What we're looking for really are particular trends or patterns in a family history. So the family history is indeed very important. Most of the time, however, the family history will not tell us about any problems. And, in fact, when we're talking about recessive genetic problems, the family history is usually within normal limits. Sometimes people come for counseling and screening because of a positive family history. Some people just come for screening tests to determine carrier status. We're talking now about tests that are simple, inexpensive, and accessible because they are easy to perform. Tay-Sachs, sickle cell anemia, and thalassemia lend themselves to screening. When we talk about genetic screening, we're thinking about the possibility of gene frequency, how common a gene is in a particular population or an ethnic group.

Q. One gene that affects the hemoglobin is specifically identified as the thalassemia gene?

A. Yes, which comes from the Greek meaning sea. It's also known as Coolers anemia, named after Dr. Cooley, who discovered this disorder in 1920. Thalassemia is a recessive genetic disorder that is caused by altered hemoglobin synthesis.

Q. What is the difference between the ethnic background and family history?

A. A family history is the story of one individual family, whereas an ethnic group is a sociocultural group or subpopulation. I think the family history will bring an individual or a family into the doctor's office with questions such as, "Am I at risk? Will my children be at risk for this disorder?" A positive family history usually results in medical consultation.

Q. How are you using the term "positive" in this instance?

A. I'm using the term positive to say that there is a history or documentation of a particular disorder. That would be a positive history for me. I think that when we talk about positives and negatives, medical terms are loaded. If you want an example of a positive gene that you carry, one that doesn't have a negative connotation, think about your own blood group. When you talk about illness and medicine, everybody thinks of disease, negativity, and discomfort. But if you think about a particular trait that we've all been tested for, that would be your blood group. You know your blood group, and blood groups are genetically determined. I don't think any of us feel uncomfortable about saying we're blood group A, B, or O, and we're RH positive or negative. All of these groups are programmed by genes. When we have no family history, we're talking about individuals who are walking around who really think about this disorder because they've either seen a poster or read about it. Or they just come into the doctor's office, and in taking their medical history, you ask, "What's your background? Where do your ancestors come from?"

Q. That would get to the ethnic background?

A. That's exactly right, as opposed to the family background.

Q. We then should be aware of our ethnic background as much as we can?

A. I think you should know about it.

Q. If we find that we carry some malfunctioning recessive gene but do not mate, do we as single individuals have to worry?

A. Not really.

Q. Would ileitis and colitis be exceptions in this case for the individual, inasmuch as these conditions are referred to as genetic?

A. You've now leaped from single gene problems to conditions we call polygenic. When we look at such disorders as colitis, diabetes, and hypertension, they may be familial. These disorders do not follow the mathematical rules of heredity in a neat fashion. Here's where we'd give what we call empiric risks. Those are based on our best knowledge from population studies, other people's work, and what we know to be true from our own experience. Environment plays a large role in many of these disorders. In other words, there are other factors besides genes that determine the person's potential expression of these disorders. In a single gene problem, the genes are there; they can't be changed or moved around. If you mate with somebody with like malfunctioning genes, each and every time you conceive, you have a 25 percent chance of having a child with a double dose of that same abnormal gene because genes work in pairs. And you have a 75 percent chance of having a healthy child.

Q. Now that computers can give a printout of your bank account, your insurance, and your credit, I also read that we can do the same thing in the body with a genetic printout. We have no more secrets?

A. I think that's an ethical dilemma, and I personally would not like to see all of this information broadcast very loudly. I think it's important to collect data about genes and their effects. It's very difficult to devise ways to collect it that, in fact, would protect the right of the individual and his or her family. I think this is a complicated business.

Q. If you understand your background and recognize that you have, for example, diabetes from your mother's side and vascular problems from your father's side, how do you ascertain whether or not one would pass these traits on to one's children?

A. Depending on the history of the person who would be your intended mate, risks could be given to you. Essentially, having a family history of diabetes and even having diabetes yourself does not mean invariably that you are going to pass this on to your offspring. Your risk could be calculated, and some directions and instructions could be given about what you can do in terms of ensuring your own and your children's health and followup. More information would have to be known about the peripheral vascular problem before risks could be determined.

Q. Am I a candidate for genetic screening?

A. I think you're a candidate for genetic counseling to see if genetic tests or screenings are necessary.

Q. My husband developed diabetes in adulthood after our daughter was born. How safe is my daughter in trying to escape this diabetes? Can she escape it completely? She is in her thirties and is obese.

A. I don't know because I do not know the rest of your family history. If this is the only case, the risk would be low. It would be important to get good medical genetic advice and good medical input. You mentioned that your daughter is obese, and I think you're right to be concerned about this aspect of the problem. Obesity or being overweight does predispose one to have a problem later on. That's something she could work on if she's well motivated and would entrust herself to the care of a physician. There are tables a geneticist could show you, and essentially what you would see is that the more first-degree relatives you have in other words, the more close relatives you have there would be a likelihood that at some point in your lifetime you would be at increased risk over the general population of developing diabetes. One parent would lessen the likelihood. This could all be calculated.

Q. I was told by my doctor that the healing time for the broken bones in my arm would depend upon my genetic structure. Is that correct?

A. I would think it would have something to do with it. But the doctor is telling you that we're all individuals, and that each of us is made up of different genes that predispose us, for example, to different reactions to different medicines. Many serious bone diseases are genetic disorders.

Q. Is it ever possible for human beings to overcome their internal environment or genetic code?

A. I don't think there's a way to overcome your genetic makeup. It's there, it's set, and you really can't change it.

Q. Does the research with recombinant DNA indicate that we will be able to reprogram people?

A. This work will enable us to better diagnose and treat people. It is in its earliest stages. Other work is now in progress. For example, let's consider Gaucher's disease. This is a storage disorder on which people are working right now to devise replacement therapy as well as to alter, decrease, or stop the storage of chemical material that builds up in major organs and in bones. If treatment were available, affected persons would be able to live a more comfortable life With respect to thalassemia, physicians are giving certain chelating agents. These agents bind iron, which is the main problem for people with this severe anemia. In other words, doctors are attempting literally to remove iron from the body with a kind of magnet effect to prevent iron overload.

Q. Is there any work being done in the field of vision to correct eye problems caused genetically?

A. There's an enormous amount of work going on to see what basic biochemical and neurologic defects are involved in eye defects. There's also technical work going on, such as attempts to replace the abnormal or malfunctioning parts of the eye.

Q. Are there actually people who, because of genetic counseling, do not marry and have children?

A. Yes, there are some people who make that judgment. The figures are low, however, because most people do not seek genetic counseling before marriage; however, that is increasing now. On the other hand, some people might marry and decide not to have children. Others may adopt or have children by artificial insemination. These are all viable options.

Q. My grandson is 14 and has ileitis and Mediterranean anemia. Will these problems go away, or are they hereditary?

A. In terms of the Mediterranean anemia, it is a genetic condition; there's no question about that. Ileitis often has a familial tendency. Again, you could sit down with a geneticist, go over the family history, and see if there is a connection between your grandson's problems and other members of the family. There are genetic services available throughout the United States.

Q. Does marijuana affect the sperm count in males, or does it cause any genetic effect?

A. I know of no untoward effects of marijuana on genes.

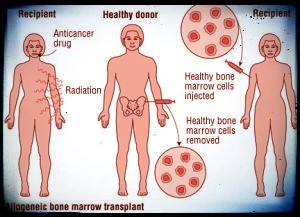

Q. Are there prenatal tests for sickle cell?

A. Some researchers at the City of Hope National Medical Center in California have developed a new technique that sounds promising. They are able to track abnormal changes in single or individual links in the complex chemical chains that make up the DNA. The test can be used on pregnant women who may be carriers of various genetic diseases. These diseases include beta-C-hemoglobin, which is similar to sickle cell anemia, and beta-O-thalassemia. The test involves amniotic fluid from the pregnant woman's uterus and extracting fetal DNA from certain cells in the fluid. Then synthetic gene fragments are introduced one that is normal and the other a replica of the defective gene being sought to the DNA. The normal can only combine with the normal pair, while the abnormal can only combine with the defective gene pair. If the DNA binds only to the abnormal pair, the fetus has the disease.

Q. Are there such things as criminal genes?

A. This is a very debatable question. A psychiatrist researcher from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a Swedish researcher, Michael Bohman, of the University of Umea have speculated that criminal genes probably involve the inheritance of such traits as impulsiveness, restlessness, and a low threshold of boredom. They studied the lives of more than 1500 Swedish adoptees born between 1930 and 1949, and found that 7 percent of those with a bad early environment and a noncriminal ancestry became criminals. Of those, 12 percent with a good early environment and a law breaking biological parent turned to crime. But bad genes combined with a bad environment produced a 40 percent risk of run-ins with the law. The conclusion from this study would seem to be that a bad environment combined with bad genes will have an influence for criminal behavior.

Q. In genetic screening, can one see a gene?

A. No, not in human beings. You are only screening the effect of that particular gene or the product of the gene, such as an enzyme, which you can see and define chemically. You measure its activity presence or absence. That's what these tests are about.

Q. How is genetic screening done, and is it always done based on some suspicion concerning someone's background?

A. It comes about in several ways. It would be miraculous to screen every gene that one has, to know a human being's total genetic makeup by means of an overall comprehensive test. But at this time we can't do that. With respect to individual counselors, we look for particular trends in a family history. Much of the time the family history will not reveal any problems. Genetic screening in the general population is geared at testing healthy individuals, newborns or adults, for a particular genetic trait or characteristic. These tests are based on the probability that the gene is present or how common a gene is in a particular population or an ethnic group.

Q. When there is a genetic screening, what do you take from the person or what do you examine in the person?

A. Usually some body fluid such as blood or urine is taken. We examine blood or that portion of blood called serum. Serum is the colloidal fluid, if you will, of the blood itself. Sometimes we use the cells of the blood. We perform analyses on white or red cells depending on the particular disorder in question.

Q. You then take the blood from the person and analyze it, and if it doesn't do certain things it's supposed to do, that's how you know something is wrong?

A. It's not the blood itself. We're testing the components of the blood to see if it contains certain ingredients. For example, we look for certain enzymes or chemicals that are in these cells, that should be there in a certain amount. We have standards by which we can assay whether there is too little there, or just the right amount, and so forth.

Q. Does age or sex matter? For example, would you find the same components in the blood of a 70 year old as in a 30 year old?

A. For all intents and purposes, in terms of what I would be measuring, yes. Now there may be some differences in terms of amounts, but in terms of my work there would be no problem. We can also look directly at the bundles of genes or chromosomes. This would constitute another type of genetic screening test that could be performed.

Q. Is there any sort of cure for Tay Sachs disease now?

A. No.

Q. Do genes affect one's personality? Do we tend to be angry, stubborn, or mean because of our genes?

A. There are some genes that are involved with affective disorders such as manic depression. I don't know of genes affecting one's general temperament.

Q. Is schizophrenia a genetic condition?

A. There may be genetic background. Again, the individual's family history should be reviewed.

Q. Do the power and speed of the healing of broken bones have anything to do with one's genetics?

A. Yes, our different genes predispose us to react differently. We are all unique based upon our different genetic makeup. Rates of healing and the way our teeth erupt, for example, are all in part genetically determined. There are also genetically determined bone diseases.

Q. Is fortified vitamin D helpful or nourishing for bone disease?

A. It depends on the type of bone disease. Individual cases require personal consultations with the patient's doctor.

Q. When my grandson was in elementary school and the class was asked to stand up, he found he could not. He had temporary paralysis. It occurred again when he entered college. Is this condition a genetic disorder?

A. There is a genetic disease called periodic paralysis, which with proper management can be successfully handled. This is a disorder that neurologists can handle with a measure of success.

Q. Is sickle cell anemia only limited to the black population?

A. Sickle cell disease has its highest incidence in the United States in the black population, but it is certainly not limited to blacks worldwide. The incidence of sickle gene in the black American is about 8 to 9 percent. However, if you look worldwide, there are areas where there is significant incidence of sickle cell, such as the Mediterranean, Greece, the Middle East, Kuwait, and parts of India.

Q. I know blacks can have thalassemia. Can they also have Tay Sachs disease?

A. It is possible.

Q. Is genetic screening or gene testing for employment justified, or is it a device for discrimination?

A. If you have a specific health related reason for doing screening, then it's justified. If you're doing it for some vague reason without clearcut goals and objectives, then I don't think it's justified at all. When screening programs have been set up with more enthusiasm than thought, we've been burned. Occasionally, results of such tests have been used indiscriminately. So you have to be very concerned about why these tests are being done.

Q. Cystic fibrosis is reported to be a genetic disease. Can you explain the cause of this defect?

A. Cystic fibrosis today is a genetic disease. In spite of extensive research, we do not know what the basic gene defect is. The work on cystic fibrosis in the last 15 years, however, has increased our understanding of the disorder and has improved the life expectancy of affected individuals.

Q. Can prescreening or pretesting before birth establish the ratio of risk with cystic fibrosis as with a number of other genetic diseases?

A. No, at this point there is no prenatal diagnosis. The only way you can estimate the risk of inheritance is through family studies, the classic Mendelian studies. But there is a problem in going back to previous generations because cystic fibrosis was not identified as a disease until 1938, and it mimics many other diseases.

Q. What type of genetic problems do we associate with Italians and Greeks?

A. Thalassemia is the term for hemoglobin disorders that are frequent in this population, which incidentally includes people of North African extraction and also extends over to Southeast Asia and parts of India. There are different types of thalassemia, a disorder of hemoglobin synthesis.

Q. Do we come into the world with harmful genes if we have no recognizable disorders?

A. Each of us has eight or nine so-called recessive genes. These genes are mutated, changed, or altered. They are generally silent or hidden. It's important, however, to have these genes. It's not bad that you carry them. They're just there, and they're part of your makeup. I believe that genetic heterogeneity strengthens our general health.

DNA Technology: Genetic Screening & Probes | A-level Biology

Q. Are blood groups determined by genes?

A. Yes, they are all programmed by genes.

Q. What is meant by the slogan we sometimes see on posters that reads, "You are or may be carrying a walking time bomb?"

A. This is kind of a dramatic statement, which to me is very alarming, because we don't want to frighten people about themselves or their future. We want them to be concerned and to understand, so that they will be responsible for their future decisions. For example, if by chance you carry a particular gene and then meet and mate with someone who carries the same like malfunctioning gene, there might be a problem. People should be informed of their risks whenever possible.

Q. Can you tell us a few more factors that are involved in genetic counseling and screening?

A. What we're looking for really are particular trends or patterns in a family history. So the family history is indeed very important. Most of the time, however, the family history will not tell us about any problems. And, in fact, when we're talking about recessive genetic problems, the family history is usually within normal limits. Sometimes people come for counseling and screening because of a positive family history. Some people just come for screening tests to determine carrier status. We're talking now about tests that are simple, inexpensive, and accessible because they are easy to perform. Tay-Sachs, sickle cell anemia, and thalassemia lend themselves to screening. When we talk about genetic screening, we're thinking about the possibility of gene frequency, how common a gene is in a particular population or an ethnic group.

Q. One gene that affects the hemoglobin is specifically identified as the thalassemia gene?

A. Yes, which comes from the Greek meaning sea. It's also known as Coolers anemia, named after Dr. Cooley, who discovered this disorder in 1920. Thalassemia is a recessive genetic disorder that is caused by altered hemoglobin synthesis.

Q. What is the difference between the ethnic background and family history?

A. A family history is the story of one individual family, whereas an ethnic group is a sociocultural group or subpopulation. I think the family history will bring an individual or a family into the doctor's office with questions such as, "Am I at risk? Will my children be at risk for this disorder?" A positive family history usually results in medical consultation.

Q. How are you using the term "positive" in this instance?

A. I'm using the term positive to say that there is a history or documentation of a particular disorder. That would be a positive history for me. I think that when we talk about positives and negatives, medical terms are loaded. If you want an example of a positive gene that you carry, one that doesn't have a negative connotation, think about your own blood group. When you talk about illness and medicine, everybody thinks of disease, negativity, and discomfort. But if you think about a particular trait that we've all been tested for, that would be your blood group. You know your blood group, and blood groups are genetically determined. I don't think any of us feel uncomfortable about saying we're blood group A, B, or O, and we're RH positive or negative. All of these groups are programmed by genes. When we have no family history, we're talking about individuals who are walking around who really think about this disorder because they've either seen a poster or read about it. Or they just come into the doctor's office, and in taking their medical history, you ask, "What's your background? Where do your ancestors come from?"

Q. That would get to the ethnic background?

A. That's exactly right, as opposed to the family background.

Q. We then should be aware of our ethnic background as much as we can?

A. I think you should know about it.

Q. If we find that we carry some malfunctioning recessive gene but do not mate, do we as single individuals have to worry?

A. Not really.

Q. Would ileitis and colitis be exceptions in this case for the individual, inasmuch as these conditions are referred to as genetic?

A. You've now leaped from single gene problems to conditions we call polygenic. When we look at such disorders as colitis, diabetes, and hypertension, they may be familial. These disorders do not follow the mathematical rules of heredity in a neat fashion. Here's where we'd give what we call empiric risks. Those are based on our best knowledge from population studies, other people's work, and what we know to be true from our own experience. Environment plays a large role in many of these disorders. In other words, there are other factors besides genes that determine the person's potential expression of these disorders. In a single gene problem, the genes are there; they can't be changed or moved around. If you mate with somebody with like malfunctioning genes, each and every time you conceive, you have a 25 percent chance of having a child with a double dose of that same abnormal gene because genes work in pairs. And you have a 75 percent chance of having a healthy child.

Q. Now that computers can give a printout of your bank account, your insurance, and your credit, I also read that we can do the same thing in the body with a genetic printout. We have no more secrets?

A. I think that's an ethical dilemma, and I personally would not like to see all of this information broadcast very loudly. I think it's important to collect data about genes and their effects. It's very difficult to devise ways to collect it that, in fact, would protect the right of the individual and his or her family. I think this is a complicated business.

Q. If you understand your background and recognize that you have, for example, diabetes from your mother's side and vascular problems from your father's side, how do you ascertain whether or not one would pass these traits on to one's children?

A. Depending on the history of the person who would be your intended mate, risks could be given to you. Essentially, having a family history of diabetes and even having diabetes yourself does not mean invariably that you are going to pass this on to your offspring. Your risk could be calculated, and some directions and instructions could be given about what you can do in terms of ensuring your own and your children's health and followup. More information would have to be known about the peripheral vascular problem before risks could be determined.

Q. Am I a candidate for genetic screening?

A. I think you're a candidate for genetic counseling to see if genetic tests or screenings are necessary.

Q. My husband developed diabetes in adulthood after our daughter was born. How safe is my daughter in trying to escape this diabetes? Can she escape it completely? She is in her thirties and is obese.

A. I don't know because I do not know the rest of your family history. If this is the only case, the risk would be low. It would be important to get good medical genetic advice and good medical input. You mentioned that your daughter is obese, and I think you're right to be concerned about this aspect of the problem. Obesity or being overweight does predispose one to have a problem later on. That's something she could work on if she's well motivated and would entrust herself to the care of a physician. There are tables a geneticist could show you, and essentially what you would see is that the more first-degree relatives you have in other words, the more close relatives you have there would be a likelihood that at some point in your lifetime you would be at increased risk over the general population of developing diabetes. One parent would lessen the likelihood. This could all be calculated.

Q. I was told by my doctor that the healing time for the broken bones in my arm would depend upon my genetic structure. Is that correct?

A. I would think it would have something to do with it. But the doctor is telling you that we're all individuals, and that each of us is made up of different genes that predispose us, for example, to different reactions to different medicines. Many serious bone diseases are genetic disorders.

Q. Is it ever possible for human beings to overcome their internal environment or genetic code?

A. I don't think there's a way to overcome your genetic makeup. It's there, it's set, and you really can't change it.

Q. Does the research with recombinant DNA indicate that we will be able to reprogram people?

A. This work will enable us to better diagnose and treat people. It is in its earliest stages. Other work is now in progress. For example, let's consider Gaucher's disease. This is a storage disorder on which people are working right now to devise replacement therapy as well as to alter, decrease, or stop the storage of chemical material that builds up in major organs and in bones. If treatment were available, affected persons would be able to live a more comfortable life With respect to thalassemia, physicians are giving certain chelating agents. These agents bind iron, which is the main problem for people with this severe anemia. In other words, doctors are attempting literally to remove iron from the body with a kind of magnet effect to prevent iron overload.

Q. Is there any work being done in the field of vision to correct eye problems caused genetically?

A. There's an enormous amount of work going on to see what basic biochemical and neurologic defects are involved in eye defects. There's also technical work going on, such as attempts to replace the abnormal or malfunctioning parts of the eye.

Q. Are there actually people who, because of genetic counseling, do not marry and have children?

A. Yes, there are some people who make that judgment. The figures are low, however, because most people do not seek genetic counseling before marriage; however, that is increasing now. On the other hand, some people might marry and decide not to have children. Others may adopt or have children by artificial insemination. These are all viable options.

Q. My grandson is 14 and has ileitis and Mediterranean anemia. Will these problems go away, or are they hereditary?

A. In terms of the Mediterranean anemia, it is a genetic condition; there's no question about that. Ileitis often has a familial tendency. Again, you could sit down with a geneticist, go over the family history, and see if there is a connection between your grandson's problems and other members of the family. There are genetic services available throughout the United States.

Q. Does marijuana affect the sperm count in males, or does it cause any genetic effect?

A. I know of no untoward effects of marijuana on genes.

Q. Are there prenatal tests for sickle cell?

A. Some researchers at the City of Hope National Medical Center in California have developed a new technique that sounds promising. They are able to track abnormal changes in single or individual links in the complex chemical chains that make up the DNA. The test can be used on pregnant women who may be carriers of various genetic diseases. These diseases include beta-C-hemoglobin, which is similar to sickle cell anemia, and beta-O-thalassemia. The test involves amniotic fluid from the pregnant woman's uterus and extracting fetal DNA from certain cells in the fluid. Then synthetic gene fragments are introduced one that is normal and the other a replica of the defective gene being sought to the DNA. The normal can only combine with the normal pair, while the abnormal can only combine with the defective gene pair. If the DNA binds only to the abnormal pair, the fetus has the disease.

Q. Are there such things as criminal genes?

A. This is a very debatable question. A psychiatrist researcher from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a Swedish researcher, Michael Bohman, of the University of Umea have speculated that criminal genes probably involve the inheritance of such traits as impulsiveness, restlessness, and a low threshold of boredom. They studied the lives of more than 1500 Swedish adoptees born between 1930 and 1949, and found that 7 percent of those with a bad early environment and a noncriminal ancestry became criminals. Of those, 12 percent with a good early environment and a law breaking biological parent turned to crime. But bad genes combined with a bad environment produced a 40 percent risk of run-ins with the law. The conclusion from this study would seem to be that a bad environment combined with bad genes will have an influence for criminal behavior.

Comments

Post a Comment